It is estimated that 1 in 2 Canadians will get cancer in their lifetime and 1 in 4 will die from the disease.

Canadian Cancer Statistics, 1987 – 2020

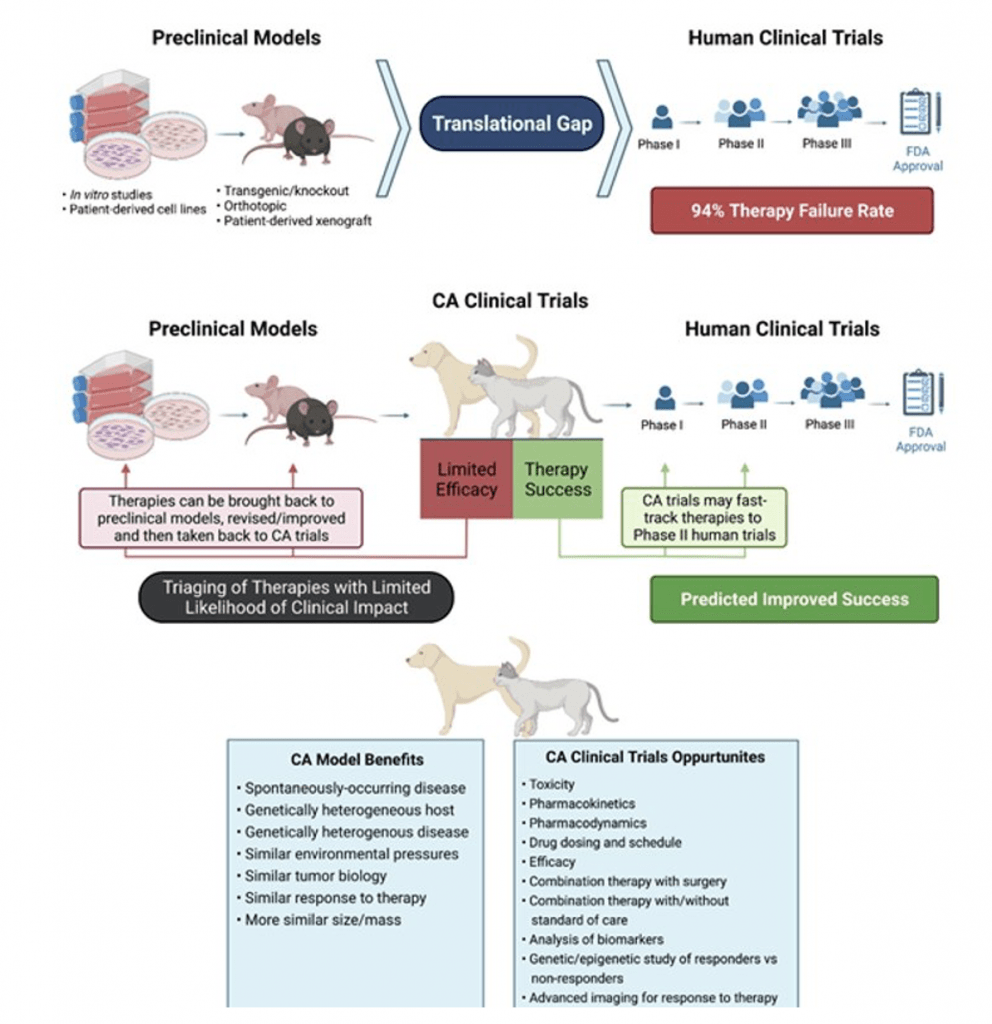

Development of new and effective therapies for cancer patients is one of the most pressing medical challenges we face today. Currently, cancer therapies developed with traditional preclinical rodent models have a 94% failure rate in generating therapeutic benefit in human clinical patients. While the current rodent models have relevance and are important in the therapy development pipeline, they have several limitations, including genetic homogeneity, size and biological complexity differences, as well as lack of spontaneous cancer occurrence. Part of the low therapy success rate is attributed to an absence of predictive translational models that more closely replicate human cancer progression and response to therapy.

Companion Animals as Translational Models

Companion animal cancer patients offer an unparalleled opportunity to study human cancers.

Companion animals have phenotypic diversity of naturally-occurring diseases similar to humans. Dogs develop many of the same cancers as humans and genomic analysis has shown that human and dog cancers have similar gene expression profiles.

In addition, the cancers are similar biologically, histologically, and in clinical course, setting companion animals apart from other mammals as models of human disease.

Companion animal cancer patients have been shown to be important predictive models of human disease progression and response to therapy and there is growing work that shows including them in the therapy development pipeline is critical.

Companion animal studies provide a crucial complement, and a not replacement, of preclinical rodent model research.

The National Institutes of Health in the US has identified the importance of spontaneously-occurring cancers in companion animals as translational models of human cancer and recently funded a brain cancer clinical trial in dogs with spontaneously-occurring disease; with a goal to fast-track development of novel therapies in human brain cancer patients.

Our human clinical research collaborators have identified the importance of including companion animal patients in the development pipeline. We have precedence in this area with a human breast cancer vaccine evaluated in cats. Another example is a novel therapy for advanced-stage ovarian cancer we have developed. Treatment options for ovarian cancer have not changed in 40 years. This work will soon progress to companion clinical trials at the Animal Cancer Centre. Our clinical collaborators are very excited about the opportunity to work with our translational oncology group to bring this therapy to a human clinical trial. As a result of this work we anticipate the ability to significantly accelerate progression to Health Canada approval.

Improvements to Therapy Development

In order for this translational research to reach its full potential, the need is clear. Cancer researchers must be able to conduct the highest-quality studies with the preclinical models and following this, we must then be able to test, revise, and refine the therapeutic intervention in our companion animal clinical trial patients. As a result of this work, we will then be able to take comprehensively-tested therapies to human clinical trials, enhancing the success rate; which will greatly reduce the cost of cancer treatment and provide more effective cancer therapies for patients that desperately need them.